Table of Contents

Intro

Bokh (in native scripts: Бөх, бөхийн барилдаан, ᠪᠥᠬᠡ) and the other Mongolian wrestling styles have had an impact on grappling traditions in Asia and Europe that can hardly be overstated.

Yet this cultural influence has been largely ignored by many. Indeed, the toll in human lives that the Mongol empire’s advance took on the world inevitably gets the spotlight. It also made them a lot of enemies in the long run, who were hellbent on preventing another Mongol unification by whatever means necessary.

In this article we are going to get you acquainted with the wrestling style that helped get Genghis Khan’s armies in shape for their famed conquests. We’ll also try to shed some light on what place it holds in the culture of contemporary Mongols, and what it took to preserve it.

1. Origins of Bokh & place in Mongolian culture

Wrestling has ancient traditions in the Mongolian plateau

One thing is for sure – wrestling has been around for a long time in the territory of present day Mongolia. Petroglyphs in Dundgovi province and cave paintings in the Bayankhongor Province show depictions of wrestling dating back to the Neolithic and Bronze ages. However, whether the people who practiced it were Mongols is not sure.

Non-Mongols might have made some early contributions to the development of Mongolian wrestling

For example, the next evidence of the existence of traditional wrestling in the later periods appears in the form of bronze plates discovered in the ruins of the Xiongnu empire (206 BC–220 AD). It was a confederation of nomadic peoples, but to this day their ethnic makeup is still unclear. Likely, they were a mix of Mongols and Turkic peoples (who by the way are also known to hold wrestling in especially high regard). What is known about the Xiongnu is that their raids were so fierce that they became the reason for the construction of the Great wall of China.

For the subsequent Xianbei empire and Rouran Khaganate the situation is similar as it has been difficult for researchers to pinpoint the ethnic composition of these states. However, it’s certain that they had a sizable Mongol population.

The Mongolian wrestling that we know now is likely a result of the unification of Mongols in the 13th century

The above-mentioned empires were rather closer to military alliances than to the modern notion of a country. At this point in time, people were organized in clans or tribes and probably didn’t consider themselves as one nation or ethnic group. What scientists use in order to categorise them together is common language and customs.

Many of the Mongol clans were hostile to each other, and didn’t come to unite in a common state until the beginning of the 13th century. It took a leader from the likes of Genghis Khan to finally unite them. After the division was over it is likely that there was a convergence of traditions between the separate tribes which led to the formation of the current Mongolian wrestling styles.

The practice of wrestling wasn’t restricted to a warrior class

So upon originating (during the Neolithic, or earlier) as probably a recreational pastime or ritual, wrestling later became part of military training. But unlike with other martial arts (like Jiu Jitsu which initially used to be reserved only for the Samurai), that didn’t make Mongolian wrestling more inaccessible to the population as the societies of these states were highly militarized anyway.

2. Mongolian wrestling surviving over the ages

One translation of Bokh is “durability” and it sure had to endure a lot to continue its existence.

Plagued by bad reputation

Now, Genghis Khan has a reputation that precedes him. In creating the largest contiguous empire to date, his armies are considered to have done irreversible damage to whole societies and cultures. Some have even pointed out that the resulting reduction in population led to such significant drop in CO2 emissions that it cooled the planet for a period of time.

While that may be true, his campaigns also triggered a sort of cultural cross-pollination between distant civilizations that might otherwise not have happened for a very long time.

One example of the results of these processes is the emergence of Kushti wrestling in India. The Mughals conquered India in the 16th century. Since they had absorbed a lot of the Persian customs, as the popular version goes, they imported some Persian wrestling know-how in the freshly conquered India. When that got mixed with the local Mala Yudha tradition, Kushti was born. But since the Mughals consider themselves to be descendants of Genghis Khan it’s likely that they brought in elements of Mongolian wrestling as well. And one can expect a similar pattern in other places that interacted with the Mongols.

But the quick and brutal expansion of the Mongol empire has had its historical price. As stated earlier, it made the Mongols a lot of enemies in the long run. Han (the ethnic majority of modern day China), Manchu and Russians, just to name a few, have been suspicious of the various Mongol ethnicities ever since, and appear to have been actively sabotaging their attempts for uniting again.

And in fact it’s easy to understand the anti-Mongol biases of some societies, considering their tragic experiences. But being objective always requires taking a closer look at one’s motives before we try and judge them.

Life in the steppes

Nations are often shaped by their surroundings – the environment they live in and the influences of their neighbours. The Mongolian plateau is characterized by an extreme continental climate that (even considering modern advances) makes it very difficult to rely on agriculture for survival. Hence the nomadic pastoralism lifestyle that has been traditional for Central Asia, and is still estimated to be practiced by up to 30% Mongolian citizens.

The routine of a livestock herder, as opposed to that of an agricultural worker, lends itself very well to practicing wrestling. Make no mistake – it’s backbreaking work (here is a great summary of all the daily chores) but while waiting for the animals to graze you have time to wrestle your siblings – many start this pastime as early as 5 years old. It helps them to both kill some time and gain the strength to manhandle the animals. So for the nomads, wrestling really is a part of daily life.

But although less susceptible than crops, livestock too is not immune to nature’s whims. The extreme conditions of the Central Asian steppes sometimes set the stage for natural disasters known in Mongolia as zud (зуд). These events involve either extreme cold, drought or excessive show/ice, preventing the animals from grazing, and leading to huge losses.

Nowadays, such catastrophes force families who lost their entire herds to migrate to the capital where they are hardly employable and often live a life of poverty, sometimes having to resort to crime.

In the old times there was no such luck. The options were limited to either starving to death, or raiding a neighboring territory – usually China.

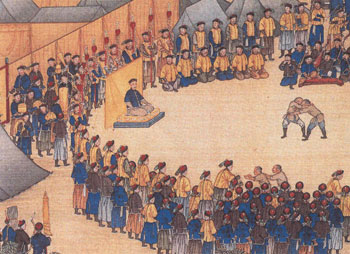

Mongols and China

The Mongols’ relationships with the Chinese were complicated. In peaceful times there was trade between the two – the Mongols needed textiles and certain foods, and the Chinese wanted horses, that were bred in the steppes, for their armies. Of course, the Chinese had more leverage when it came to negotiating, since they could potentially breed their horses on their own. It turns out dissatisfied business partners can make bad enemies, as the Mongols at one point conquered the whole of China and ruled over it for nearly a 100 years through the Yuan dynasty.

But after that did come to an end, the Mongols continued their inter-clan rivalries and eventually got conquered by Manchu-led Qing China.

During the later years of Qing rule the state took an oppressive stance towards Mongols, which was formalized by the so-called New policies. These basically fostered Han Chinese settling in predominantly Mongol territories, probably in a bid for assimilation. What worsened the situation for Mongols was that the state now started to demand its taxes in silver rather than livestock. To be able to pay, Mongols had to first trade their animals for silver with the Han Chinese merchants. And guess who once again had the better leverage in these deals…

Meanwhile in (Imperial and later) Soviet Russia…

Mongols living in Russian controlled territories didn’t fare much better either. The two Mongol ethnicities that reside there are the Buryats and the Kalmyks.

The Buryats of the Baikal region

Historically, Buryats have been inhabiting the area around lake Baikal. The Russians first attacked their territories in the 17th century and had successfully conquered them by the 18th century. During the Russian civil war, many Buryats fought against the Bolsheviks, so naturally they were in for a bad time when the Soviets finally prevailed. A failed revolt in 1929 further worsened their position as they ended up getting the complete Stalinist treatment. This included purges, killings, forced resettlement, removing the name “Mongol” from the title of their Republic, and a ban on using Mongolian script.

The Kalmyks around the Volga

Kalmyks – the other Mongol group living in the bounds of Imperial Russia and the subsequent USSR, are descendants of Oirats who migrated from western Mongolia to the banks of the Volga River in the beginning of the 17th century. Initially they allied with the Russians but were later annexed by them and stripped of their autonomy. The empire started settling Russians and Germans in their territories, while at the same time pressuring the Buddhist Kalmyks to adopt Christianity, and expecting them to serve as cavalry for the Imperial campaigns.

Seeing where all this was going, in the end of the 18th century, a large group of Kalmyks (170 000 to 200 000) decided to migrate back to Mongolia. The Russian empress however, considering them as her subjects, didn’t approve of the idea and sent some of her vassal troops against them. Only about a third of the Kalmyks who left managed to make it to their destination, which was then controlled by Quing China. The ones that did arrive got forcefully resettled so as not to form a big community.

Overall, the period after the collapse of the Mongol empire, and before Mongolian independence (maybe even until the democratic revolution) was not a great time to be Mongol. With such prejudice and assimilation pressures it must not have been easy to preserve precious traditions such as their folk wrestling.

2.1 The Naadam festival

Being a nomadic culture, it can be hard to sustain ties and a sense of belonging like those of a sedentary community. Over the difficult years described above, folk festivals have played a key role in supporting the Mongol peoples in safeguarding their identity. The associated competitions are also the moment when even non-participants can enjoy the art of Bokh, albeit only by watching.

Even now, in a world where the nomadic lifestyle is becoming less and less relevant, one of the main means applied to preserving Mongolian traditional wrestling are the festivals or Naadam (Наадам).

Mongolian wrestling or Bokh is part of the so-called “Three Manly Games” (эрийн гурван наадам), together with cross-country horse racing and archery. The wrestling tournament is the most popular part of the whole event.

Naadam is in plural

People who are very vaguely familiar with contemporary Mongolian culture think of the Naadam as one event – the major competition that is usually held in July. In actuality, Naadam translated literally means games/competitions, and there are two major ones in the summer and many regional ones, organized by each province or city.

Arguably, the most famous one is the Naadam of July 11 to 13, held in Ulaanbaatar. It’s known as National Naadam, and originally commemorated the People’s Revolution of 1921. That very fact has sparked some controversy, so the state has declared it to also be dedicated to several other important historical events: the foundation of Mongolian statehood, Mongol Empire, Restoration of National independence in 1911 and the Democratic Revolution.

The other major Naadam is again held in the capital, but during August. It started as a complementary event to a Buddhist ritual known as Danshig offerings. Tracing its origins back to 1912, this festival is now known as the “Danshig Naadam”. Since its recent re-establishment it has been dedicated to Zanabazar – a spiritual leader of Buddhism in Mongolia.

Now, obviously both these festivals have roots, tracing back since long before their formal commencements in the 20th century. One might argue that despite being officially dedicated to political or religious events & figures, their foundations lie in Mongolian culture itself.

Probably the biggest traditional wrestling events in the world

Mongolia’s National Naadam might just qualify as the biggest traditional wrestling event in the world. With no weight classes and a roster of up to 1024 wrestlers during anniversary years (and 512 in regular years).

In fact, Mongolian wrestling does hold the Guinness world record for what was arguably the wrestling tournament with most participants ever. The event was held in 2011 and featured 6002 wrestlers. It’s no surprise it lasted 9 days. In the end, Chimedregzen Sanjaadamba triumphed and took the grand prize of about $12 000.

Ranking system (but no belt exams)

Bokh has a ranking system. But unlike in some martial arts where you can advance after taking an exam with your instructor, in Mongolian wrestling you have to earn your promotion via a good performance in a tournament.

In the Naadam, for practical reasons, all matches are contested at the same time, meaning that the competition is structured in rounds/stages. If you lose a match, you’re eliminated from the tournament. Thus, an anniversary year Naadam, with 1024 participants, will take 10 rounds to produce a champion:

- Round 1 – 1024 wrestlers

- Round 2 – 512 wrestlers

- Round 3 – 256 wrestlers

- Round 4 – 128 wrestlers

- Round 5 – 64 wrestlers

- Round 6 – 32 wrestlers

- Round 7 – 16 wrestlers

- Round 8 – 8 wrestlers

- Round 9 – 4 wrestlers

- Round 10 – the 2 remaining wrestlers clash in a match to determine the champion.

The rank a wrestler can earn depends on which round he reaches:

- “National Falcon” – for reaching round 6

- “National Hawk” – for reaching round 7

- “National Elephant” – for reaching round 8

- “National Garuda” – for reaching round 9

- “National Lion” – for reaching round 10

- and finally, “National Champion/Giant” for winning the final round.

If a wrestler manages to repeat his achievements the following years, his rank gets decorated with further epithets (such as “Grand National Champion” or “Long lasting National Champion”).

Of course National Naadam is the most prestigious Bokh competition and before thinking of participating any aspiring wrestler must have first earned a rank in the smaller provincial Naadams.

The host used to decide how to match the wrestlers

One curiosity in the organisation of Mongolian wrestling tournaments is that traditionally wrestlers were not paired randomly. The hosts have had the right to control the pairing (usually to the “home team’s” advantage). Also, high ranking wrestlers too had the power to choose their own opponents.

We can’t say which of the two interests would prevail, in case of conflict, but what is for sure is that these practices have caused some backlash. So much so that, since the 80s they have been abandoned for large events, but can still be seen in smaller competitions.

3. Rules of Mongolian wrestling Bokh

Up until now, for simplicity’s sake, we had been using the terms “Bokh” and “Mongolian wrestling” interchangeably. But coming to speak of rules an important distinction must be made.

Bokh is actually the wrestling style of the Khalkha people – the largest ethnicity within the group of Mongol peoples and the ethnic majority in the republic of Mongolia itself. The rules we will review here are those that the National Naadam is contested by.

For a quick look at the other Mongol wrestling styles you can check our dedicated bonus chapter.

3.1 What constitutes a victory in Bokh

With such immense competition pools, a complicated ruleset would be impractical for Bokh, since the tournament would take forever to produce a champion.

Probably that’s one of the reasons why a Bokh match is won simply by making the opponent touch the ground with any part of the body above the knee.

3.2 The Mongolian wrestling outfit & gripping rules

The Mongolian wrestling uniform

The signature outfit of wrestlers is one of Bokh’s trademarks. It consists of a jacket, shorts, boots and a hat. Most important are the jacket and shorts/briefs, as they are used for grips.

The jacket, called Zodog, is made of cotton and silk. It has a very unusual style, where it only covers the back, and sleeves cover the shoulders and arms, with the whole thing being fastened at the chest with a simple string. When a wrestler loses a match, he unties this string as a gesture that signifies he has gracefully accepted his defeat.

The shorts, resembling Speedos, are called Shuudag. They are made of soft leather and textile.

The boots (Mongol Gutal) are made from cow leather and can take up to 2 months to manufacture.

The hat, known as Malgai, has 4 sides representing the 4 historic provinces of Mongolia. It has a red ribbon hanging out of its back – this is a recent addition to it, and the golden stripes on the ribbon indicate the wrestler’s rank. The Malgai is worn only for ceremonial purposes and is of course taken off before the match begins.

Gripping rules of Bokh

As mentioned, grips can be taken on the opponent’s jacket and pants. The legs may also be grabbed and such grips are used for many takedowns. What you won’t see much of in Mongolian wrestling is collar ties as grabbing the neck and head is generally viewed as disrespectful.

Bokh has its own kind of sports etiquette. When a wrestler loses a match, except untying the string that holds his Zodog jacket, he is also expected to pass under the winners arm in a show of respect. However, when the loser is of a higher rank, the winner should pass under his arm, despite being victorious.

3.3 Other general competition rules

The dwellers of the open steppes are not very fond of boundaries and restrictions. This is even reflected in the rules of their wrestling style.

The competition arena

Bokh matches traditionally take place on open and flat grassy meadows, cleaned up from rocks or anything else that might harm the wrestlers. In the case of National Naadam however, the matches are contested on a big stadium so that more people can spectate.

Bokh wrestlers walk in the competition area, performing a traditional dance known as Devekh. In addition, the winner performs it on his way out. It mimics the flight of a mythical bird named Garuda – Buddhism used to be widely adopted in Mongolia. And, while to foreigners Devekh might look like just some curiosity, it’s probably a fusion between ritual and warm-up – just like Muay Thai’s Wai Kru ceremony before fights.

Match duration – as long as it takes

There’s actually no time limit for the matches, so potentially they could go on for hours. However, every wrestler and his zasuul (an in-ring aid and supporter; doesn’t have to be a coach) realize this would leave the crowd very dissatisfied.

Rarely, when the wrestlers do get too carried away with the feeling-out process and grip fighting, a fixed grip position, from which it’s easier for either wrestler to score, may be established.

Weight classes (are overrated?)

Another thing that’s characteristic of Bokh is that there are no established weight classes – you could end up wrestling someone who is twice your size. Rather than the heavier man always being at an advantage, Mongolians simply consider wrestlers of different sizes to have different kinds of strengths.

Female participation (or lack thereof)

Bokh has always been practiced exclusively by men, and continues to be so to this day.

Legend holds that the current design of the Zodog (the jacket that Bokh wrestlers wear) was adopted after a woman once participated in a competition in place of her injured brother, and wasn’t recognised because the jacket covered her breasts. So since that time, the Zodog has been leaving the chest uncovered.

3.4 Techniques

Bokh is said to have about 40 base techniques, known as mekh, but when all their variations are included, they may total to around 600.

Takedowns

When it comes to takedowns, leg grabs are used extensively. Since most of the match passes in a clinch, they usually happen in the midst of a grip breaking sequence but can also be the result of arm drags. Very often the finish is by lifting the opponent and throwing him to the ground in a Te Guruma motion, though ankle picks with very technical finishes can be seen as well.

Leg techniques (mostly hooks, sweeps are more rare due to the grip the Gutal boots provide) are just as common, with equivalents of Judo’s Ouchi Gari and Kosoto Gake often ending matches.

Most other wins are usually scored via hip throws.

Other technical aspects

Bokh doesn’t have a ground game (neither pins, nor submissions). Much like in Khapsagai and Ssireum (two of the other Asian wrestling styles that we’ve already covered), going to the ground means the end of the bout.

4 Bonus chapter: the other Mongol wrestling styles

Before Genghis Khan, the Mongols were, for the most part, a collection of rival tribes. It’s no surprise that after his death, the empire he had created quickly grew to be so decentralised that it had effectively split into several states which were starting to develop their own cultures, often influenced by the peoples they had conquered. As a result of their turbulent history, the descendants of the Mongols, who now form separate sub-ethnicities, have ended up being part of different countries even now.

A comparison between the major Mongol wrestling styles

So far, we’ve been looking at Bokh – the wrestling style of the Khalkha who are the ethnic majority in modern day Mongolia. Here we’ll do a quick comparison to show you the differences and similarities between all the main wrestling styles of the Mongols.

| Style name | Bokh | Bukh barildakh | Bukhe barildaan | Bek noldgan |

| Native name | Бөх, бөхийн барилдаан | Бух барилдах | Бухэ барилдаан | Бэк нолдган |

| Place | Mongolia (autonomous country) | Inner Mongolia autonomous region, China | Republic of Buryatia, Russian Federation | Republic of Kalmykia, Russian Federation |

| Ethnicity | Khalkha | Khorchin, Ujumchin and others | Buryats | Kalmyks |

| Grips on garments? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Grip fighting? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Leg techniques | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Leg grabs | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Pins & ground control | No | No | No | No |

| Submissions | No | No | No | No |

| Striking | No | No | No | No |

| How you win? | Make the opponent touch the ground with any part of the body above the knee. | Make the opponent touch the ground with any part of the body above the knee. | Make the opponent touch the ground with any part of the body above the knee. | Throw the opponent in such a way that both shoulder blades touch the ground |

Differences in the rules

There are two obvious differences. First, while all other major wrestling styles of the Mongols allow leg grabs, the one practiced in the Inner Mongolia region of China does not. And secondly, in Kalmyk wrestling, making your opponent touch the ground with any part of the body above the knee is not enough to win, but rather you must throw him in such a way that both shoulder blades touch the ground.

Differences in the uniforms

But beyond that, there is another area where these styles diverge from each other, and it’s one that our summary table can’t cover. All listed styles utilize grips on the opponent’s garments, but the uniforms themselves differ from the Zodog and Shuudag of Khalkha wrestling that we have shown earlier.

Inner Mongolia Mongols

In Inner Mongolia, wrestlers wear a short-sleeved jacket that leaves the chest open and ends with a belt that’s part of the jacket itself. The whole thing is made of heavy cow leather and embroidered with round silver or copper ornaments. Wide colourful pants are worn. The boots are also different than the ones in Khalkha wrestling – here, the toes are not upturned.

Buryats

The uniforms of Buryat wrestlers are more modest. They compete shirtless, in shorts, on top of which a special kind of textile harness is worn/tied. It’s used for gripping and is somewhat similar in design to the leather leg harnesses used in Icelandic Glima.

Kalmyks

And finally, the Kalmyks traditionally only wore a pair of baggy shorts, used for grips. Later, a belt was added. Kalmyk wrestling is actually the only form of Mongol wrestling that is practiced barefoot.

5 Mongolian wrestling’s influence on modern grappling

If you’ve read this far you already know that wrestling holds a major spot in Mongolians’ culture – so much so that when a male child is born, his family give their blessing to him, wishing him that he may one day grow up to become a wrestler. Even a former president of the country was a high level wrestler, also competing in Judo and even managing to become a world champion in SAMBO.

This is a pattern that’s actually very common with Mongolian wrestlers – unlike others, they do not specialize in one style and they don’t shy away from competing under several different rulesets. That has led to Mongolians becoming among the top athletes in some of the major grappling sports.

Freestyle wrestling

Olympic wrestling actually isn’t Mongolia’s most successful grappling sport (that honor goes to their judokas). That being said, as of 2022 Mongolia has 10 medals in freestyle wrestling from the Olympics (4 silver, and the rest – bronze) and 39 from the world championships (of which 3 gold).

Curiously, the country seems very underrepresented in Greco-roman wrestling, not having a single medal neither from the Olympics, nor from world championships. These results however might be due to a lack of popularity of this style, and not a lack in ability. A good point has been made in noting that during the 1974 Asian Games in Tehran, of the seven Mongolian wrestlers who participated in Greco-Roman competitions, one won silver and four won bronze medals, despite never being trained in that sport.

Judo

Mongolians are becoming a force to be reckoned with in international Judo competitions. They have won 11 medals in the Olympics, including the only gold so far for the country, and 27 medals from world championships (including 4 golds).

Sumo

For a long time now Sumo has reached popularity outside of its homeland. Mongolian wrestlers have come to be among the most successful foreigners in this Japanese sport.

To understand what we mean by that, here are two of their most important achievements:

- In 2005, Mongolian Dolgorsürengiin Dagvadorj, known Asashōryū Akinori (朝青龍 明徳), became the first man to win all six official sumo tournaments in a single year.

- In 2015, Nyamjavyn Tsevegnyam, known as Kyokutenhō Masaru (旭天鵬 勝), became the man with the most sumo wrestling bouts contested in the top division (makuuchi) – a staggering 1470 matches.

Conclusion

There are many cases where the existence of indigenous grappling styles is sacrificed for the sake of yielding medals in modern international sports. For instance as the state is more interested in representation in Olympic sports, styles like India’s Gatta gusthi are falling out of favour and left depending on a few enthusiasts to keep them alive.

The Mongols however, show a great example of how traditional wrestling can exist in symbiosis with modern sports, and moreover it can actually contribute to international success on the mat.